Great Basin Water Network Comments

|

SNWA GROUNDWATER DEVELOPMENT PROJECT

|

|

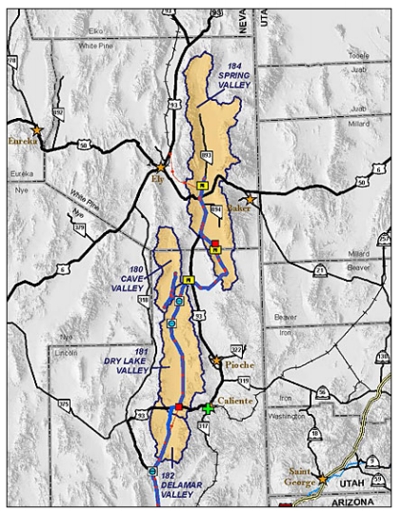

OUR WORK: We are primarily known for our work to protect rural areas from inter-basin water transfers,

particularly the Southern Nevada Water Authority’s Groundwater Development Project, which we affectionately

refer to as the Las Vegas Water Grab. We want to show you a map of the project proposal, which would run

roughly 300 miles from Las Vegas up the Eastern edge of the state. Fields of wells would pump 200,000+ acrefeet

of groundwater from valleys in Nevada and Utah, across public lands and adjacent to wilderness areas and

Great Basin National Park, and a pipeline 8 feet in diameter would deliver the water to the city.

SNWA filed applications for ALL the unappropriated water in these basins in 1989, 27 seven years ago. The

applications lay in a holding pattern until 2006, when SNWA requested the State Engineer to proceed to hearing.

The following timeline shows the various steps in the process and our successful court challenges. For the sake

of time, we will just distill some of the core issues we have with the proposal. As we look at big-picture changes

to water policy in the state, you will hear some examples relating to this project and our recommendations are

grounded first and foremost in our experience with this project. That said, we think many of the principles we’ve

identified would be beneficial to the state as a whole, and a model for the region.

Hydrologic basin boundaries and state lines almost never match up. One of the key issues with the Groundwater

Development Project is Snake Valley, home to the Nevada town of Baker, the gateway to Great Basin National

Park and shared with the State of Utah. Both states have to agree to Nevada’s plans, and so far Utah has chosen

not to sign off.

A host of federal agencies chose to sign what is called a confidential stipulated agreement, which we believe

they signed too soon without adequate guarantee that impacts to the lands would be mitigated. It was not an

open process. No public meetings were held.

A major point of contention between us and SNWA is how detailed a monitoring and mitigation plan needs to

be, to stop pumping when adverse effects start to appear. And please note that once they appear, even

stopping completely could result in damages that last for decades. These are some of the “irreversible and

irretrievable commitments of resources” that the BLM identified in its Environment Impact Statement for the

right of way to build the pipeline on federal lands. There are 4 pages in their report of these impacts that can not

be mitigated, and apparently they considered them acceptable, while we do not.

We compare this project to the LA Aqueduct, which drained California’s Owens Valley 100 years ago and now

costs urban ratepayers billions in mitigation for dust and other environmental impacts. If the SNWA project can’t

pump the full amount it intends to without dangerous environmental impacts, it would be a complete a financial

boondoggle at a total cost of at least $15 billion. We believe that there are a variety of aggressive and creative

conservation measures that would be a much better investment. And finally, while nobody wants to talk about it

because of the effects it would have on the economy, we feel it is critical to understand that we live in arid lands

and that, no matter the use and even with conservation, each water basin has a carrying capacity. We need to

plan and limit growth based on that watershed’s capacity, and stop looking for ways to take water from our

neighbors.

THE STATE LANDSCAPE: Nevada is the driest state in the nation, and its water law is designed both to reflect

that fact and to encourage prudent decision-making based on sound science. Nevada’s water law is carefully

designed with sober foresight by legislators and water managers to balance the limited nature of Nevada’s

water resources with the demands Nevada’s population places on them. These minimal standards of

sustainability were established with the State’s long-term health and economic wellbeing in mind, and cannot

be weakened without seriously jeopardizing Nevada’s long-term future. While the need to meet these bottom

line requirements has occasionally been inconvenient for the proponents of unsustainable proposals, we hope

that any attempts to modify the state’s water law build upon this foundation, not undermine it.

56 water basins in Nevada are severely overappropriated (red & yellow) |

|

Given population growth and the realities of drought and climate change, prudent decision-making grounded in

sound statutory authority is critical. With the population growth of cities, water is NOT always available. And

whether or not you believe in climate change, we are in a drought that has brought sharper focus to water

allocation. Despite the sound statutory guidance noted above, past State Engineers have too often said “YES” to

water right applications and allowed over-appropriation of water to the point that

56 of our water basins are

severely over-allocated

. There are more over-appropriated basins on the way unless the law provides clear

guidance to the State Engineer with regard to ensuring the sustainability of the State’s water resources.

Now we’ve met the drought, and it may be commonplace for the future.

The State Engineer is tasked with bringing over-appropriated basins back to equilibrium, but there is no roadmap to get there. While current law

gives the State Engineer some tools, including the controversial but legal option of enforcing water rights based

on seniority, he may need additional guidance to correct or find solutions to over-allocations. However, we

contend that the State Engineer must be guided by and bounded by the concepts of finiteness and prudence

when confronted with the decision about whether to grant new water rights. Water, especially groundwater,

must be treated as the finite, fragile and scarce resource that it is.

Are existing laws the problem? Do they need changing? OR is it the antiquated administration of the law that

needs changing? We contend it is some of both. We think the courts are saying both, too. Historically, State

Engineers set precedents for administering the law when water was comparatively plentiful. Now, it is not and

we are confronted with the new challenges associated with allocating water resources in times of scarcity.

The following are suggested policies and steps for the State of Nevada concerning the allocation or reallocation

of water:

PRUDENCE: The definition of prudence is exercising “careful management; economy; common sense.” In the

early days of our state’s history, desert-land entries were a form of homesteading used to turn federal land into

private agriculture land, provided the land could be cultivated and irrigated. The prudent course of State

Engineers past would have been to assume 100% of these entries would succeed in putting water to beneficial

use, but instead they assumed half would fail and lose their water rights. Hence, over-appropriation!

Another example where prudence is an issue is signing off on subdivision maps. The State Engineer puts his seal

on each subdivision without really knowing whether or not water is available.

In hearings, State Engineers have listened to dueling experts debate the hydrology of a basin instead of giving

first and foremost consideration to peer-reviewed USGS Basin Recon Reports. These are factors in the overallocation

we see today.

Presently, the State Engineer vigorously seeks to “maximize beneficial use” In the short term. Why should he or

she “maximize” immediate use at the cost of long-term sustainability, when prudence is the only approach that

will serve Nevada’s long-term interests? When the long view is taken, it is clear that it would be far better to

use caution and to approve water rights to ensure sustainability in a basin, rather than to approve “maximized”

use that may end up depleting it. The definition of perennial yield plays a part in this, BUT the ultimate test of

hydrology is when the water is pumped. Maxing out basins guarantees maximized problems when the water

ends up over-allocated.

If the State Engineer requires new guidance from the Legislature, it should be to no longer favor loose issuance

of new water rights in order to maximize the short-term beneficial use of that water. Instead, they should use

“prudence” in allocating water in order to ensure the State’s long-term economic and environmental health. The

State Engineer also must recognize the frequency of droughts and close basins or withhold future allocation of

water in basins where current use is at or even near the sustainable capacity of the basin. We call it the 90%

solution. When a basin not over-appropriated reaches 90% of the basin’s capacity, no further water rights

should be awarded. This may help keep groundwater basins in equilibrium.

Finally, it’s important to note that the mining of ancient water is unsustainable and cannot soundly be

considered part of a sustainable water budget for a basin. It is unsustainable because it will need another glacial

age to recover. That is not something we think will occur anytime soon.

DEFINITION OF PERENNIAL YIELD: The State Engineer’s office commonly allocates water based on “perennial

yield,” but it is not defined in state law. The “commonly understood definition” seems to mean that natural

discharge (use) should be equal to natural recharge (precipitation). You’ve also heard about ETevapotranspiration.

ET is the amount of water that is sent off into the atmosphere by plants, yes, plants. This

water is now considered AVAILABLE water too. The first error here seems to be like squeezing juice from an

orange. You can’t get every drop; there’s always some left somewhere. Second, if you capture all of the water

that the plants use, they die. Then, you have no plants to hold down dust, or you may have successional plants

that may not be edible by wildlife or livestock (i.e, invasive noxious weeds). And while discharge stays relatively

constant, recharge fluctuates and may be declining in an era of scarcity. This is a recipe for over-allocation. The

water available for appropriation does NOT equal discharge/recharge. A safe, sustainable perennial yield must

be something less.

Our suggestion is that the State Engineer should allocate only as much water as is a safe, sustainable perennial

yield. This is defined as “the maximum amount of water that can be safely salvaged each year over the long

term without depleting the source or the [ecological] resources [that depend on it].” Safe sustainable perennial

yield should be determined from estimated water budgets for each hydrographic basin, understanding that

water flows under and/or across water basin boundaries.

BENEFICIAL USE:

In order to maintain a water right, it must be put to beneficial use. Current beneficial uses

include municipal and industrial, agriculture, mining, and wildlife. The definition does not include water to

sustain naturally occurring vegetation, wildlife habitat, or forage for livestock, and we believe it should.

Examples include springs, streams, creeks, wetlands and meadows, and phreatophytes. The vegetation that

meets habitat and forage needs also provides critical groundcover to prevent dust and erosion, a preventative

benefit of that “use.”

We suggest that water for recreational and scenic tourism—ponds, lakes, streams, wetlands—is also a beneficial

use. Given that man-made lakes and fountains in urban areas are considered tourist attractions, we also need

to recognize that other areas of our arid State that have beautiful water features also benefit the State’s tourism

economy. There are many very real benefits of our water resources being used by the natural system, and we

need to expand the definition of beneficial use to recognize those benefits and preserve the state for future

generations.

Disconnected surface and groundwater management

leads to double-dipping

|

|

CONJUNCTIVE MANAGEMENT – HYDROLOGICALLY CONNECTED GROUNDWATER AND SURFACE WATER MUST

BE MANAGED AS A SINGLE SOURCE: Too often, surface and groundwater have been allocated separately. It

means that double-dipping, one right from each source, has been allowed and has caused over-allocation of

water in many basins. You’ve seen and heard from many people that this part of the law needs fixing. We

concur. USGS has also pointed this out in the ”Water 101” presentation that they made to you at the first

meeting. The State Engineer must recognize connected ground and surface water as one source of water and

must base future allocations on the known combined amounts (safe, sustainable perennial yield) as indicated by

USGS hydrological reports and findings. We think this is prudent because the USGS does the scientific research

as a neutral third party. However, USGS determinations require funding up front. We would also point out here

that some of the basins targeted by SNWA’s Groundwater Development Project lie within the White River flow

system, which ends up in Lake Mead and thus creates another potential double-dipping scenario.

OVER-ALLOCATED BASINS: The State Engineer should have powers to first encourage and then enforce bringing

over-allocated water basins back into safe sustainable perennial yield. Each over-allocated basin should have 5

years to develop a plan to reach compliance with safe sustainable perennial yield. The plan should force

compliance within 10 years of completing the plan and may consider solutions outside current law to bring the

basin back into compliance. The plan must be reasonable to include seniority, buyouts, exchanges, and other

solutions without becoming precedent for any other basin. Our fear is that these new potential tools will

become an incentive to over-appropriate a basin, or be manipulated to avoid or erode the foundations of the

state’s water law.

INTERBASIN TRANSFERS: What happens when water is permanently withdrawn from its basin of origin and

pumped to a different part of the state? Senior water rights are inevitably affected. Streams, seeps and natural

meadows dry up. Vegetation used by both livestock and wildlife is lost, which also may lead to serious air

quality issues from dust, similar to what’s happened in California’s Owens Valley and Utah’s Salt Lake Valley.

Also, water use already approved in-basin is not equivalent to that approved for an interbasin transfer. In valleys

where there is irrigation, any excess applied water usually percolates back into the ground, recharging the

aquifer. In interbasin transfers, it never comes back. It’s gone. So real caution is needed.

Interbasin transfers over 1,000 AF of water raise a substantial risk of significant impacts on both the losing and

receiving basins. Nevada law recognizes this truth and wisely imposes additional requirements on such

applications. Under current Nevada law, the State Engineer must engage in a serious and thorough evaluation of

the environmental impacts in both the losing and receiving basins to be in the public interest. Existing Nevada

law also requires the State Engineer to consider the economics and the financial health of the basin of origin,

and its future growth plans. The State Engineer must also determine if the receiving basin could conserve more

water (i.e., through reuse or recycling of water, or the use of tiered conservation rate structures or other

alternatives). Finally, he or she must determine that the receiving basin has the financial capability to pay for

the interbasin project. These requirements all are prudent, but they are undermined by the fact that the State

Engineer does not have staff qualified to assess environmental or economic impacts. For the safety of the State,

these key required components of the State Engineer’s evaluation of the impacts of interbasin transfers must

remain in the law and be supported by providing the State Engineer with the necessary resources to properly

perform that evaluation.

Last, the State Engineer is responsible for the allocation of water within the State, but must consider the impacts

on linked water basins that are allocated or shared with neighboring basins in neighboring states. One example

is Snake Valley, a basin targeted by the SNWA Groundwater Development Project that is shared between

Nevada and Utah. Other implicated basins include Pahrump and Amagosa.

SPECULATION AND THE MANAGEMENT OF APPLICATIONS: Anti-speculation policies to restrain private water

developers must continue. In Nevada, water is owned by all the citizens of the State. The current law does not

allow water speculators to file applications to tie up water rights until they have identified a beneficial use. The

same line of thought, however, allows municipalities to tie up water indefinitely. It is important for

municipalities to be able to plan and hold water for some specified time in the future, but after 25 years it seems

detrimental to the economic health of the state. Areas where water might otherwise be available for a variety of

uses is kept off limits, subject to inactive water rights or applications for those rights. SNWA has had water

applications pending since 1989--that’s 27 years, and for 15 of those years no action was taken, or hearing held.

Should Southern Nevada be able to hold water applications for 75-100 years if the water is not needed for

another 30-50 years at the expense of depressing the economies of the losing basins for the same period of

time? We think a limit needs to be put in place.

PROTESTS: This is a “due process” issue where a well-funded applicant can apply multiple times and wear down

protestants who cannot afford to keep filing protests to protect their own interests, as in the cases of SNWA and

Rodney St. Clair (to name a couple). The State Engineer has the discretion to manage applicants so that

protestants are no longer at a disadvantage by having to protest, re-protest, and then re-protest again as in the

St. Clair applications. Something is fundamentally wrong with this way of doing business, and it needs to be

addressed.

FUNDING FOR THE STATE ENGINEER’S OFFICE: In the State of Nevada where water will always be an issue of

utmost importance, the Legislature must appropriate more funds for the State Engineer’s office to handle the

increased load of applications, the increased number of administrative hearings because of increased protests,

to pay the State’s share of USGS basin studies, to fully study interbasin transfer impacts, and to deal with overallocated

basins. The office has data needs, financial needs and legal needs. We encouraged and in fact asked

the legislature to approve rulemaking for the State Engineer’s office. The budget crisis that prevented that

process is over, but now we have a crisis induced by drought that is NOT getting the same attention. The State

Engineer’s staff works hard to keep up with the load. Yet despite the office’s best efforts, there is still a large

number of pending applications that have been subject to notice and protest and that the State Engineer has

not acted on.

CONCLUSION: We thank you for your time. We thank the State Engineer and this subcommittee for efforts to

make state water law better for all of the citizens of Nevada. We hope you agree that our suggestions will help

solve some of the problems with existing water allocations and with water allocations in the future. We

recognize that some of our suggestions will be very politically difficult to implement. Please also consider

whether it might be appropriate to impose a 2-3 year moratorium on the approval of new water rights

applications until improved laws and regulations can be developed and implemented. Nevada has

contemplated, discussed, yet not solved the allocation problem that has been brought into sharper relief by the

current drought. It is time for action. Let’s solve this problem rather than exacerbate it. Let’s address

challenges relating to scarcity now so that they won’t become bigger problems in the future.

Print Document [5 Page PDF] ![]() Print Power Point [17 Page 14 MB PDF]

Print Power Point [17 Page 14 MB PDF]![]()

Related Information

-

Legislative

- Website: 2015-2016 Interim Legislative Commission’s Subcommittee to Study Water

- Website - Division of Water Resources

- Nevada Water Law 101

- Overview of Nevada Water Law [44 Page PDF]

- Water Rights in Nevada: USDA/BLM

- Stipulated Agreements that DOI agencies have developed with other parties in southern and eastern Nevada

State Engineer

Federal