It just wouldn’t feel like August if federal officials weren’t bracing us for more water cuts —triggered by federal projections of reservoir elevations — for the Lower Basin at Lake Mead. Annual reductions, announced in mid-August, are baked into the current policies guiding the low-level operations of Lakes Mead and Powell.

As we’ve seen in the past five years, some Augusts are more gut-wrenching than others, depending on the preceding winter.

So after five years of enacting cuts, we must wonder: Are we really getting to the root of the problem — even as water managers prepare a new framework to run the nation’s largest reservoirs beyond 2026? For example, Lake Mead is 33 percent full, meaning one or two dry winters could have us back at the brink.

We won’t ever cut our way to a full Lake Mead. So what are we to do?

Read along and see what our coalition of NGOs is considering as we sluice through the policy channels of the west’s hardest working river.

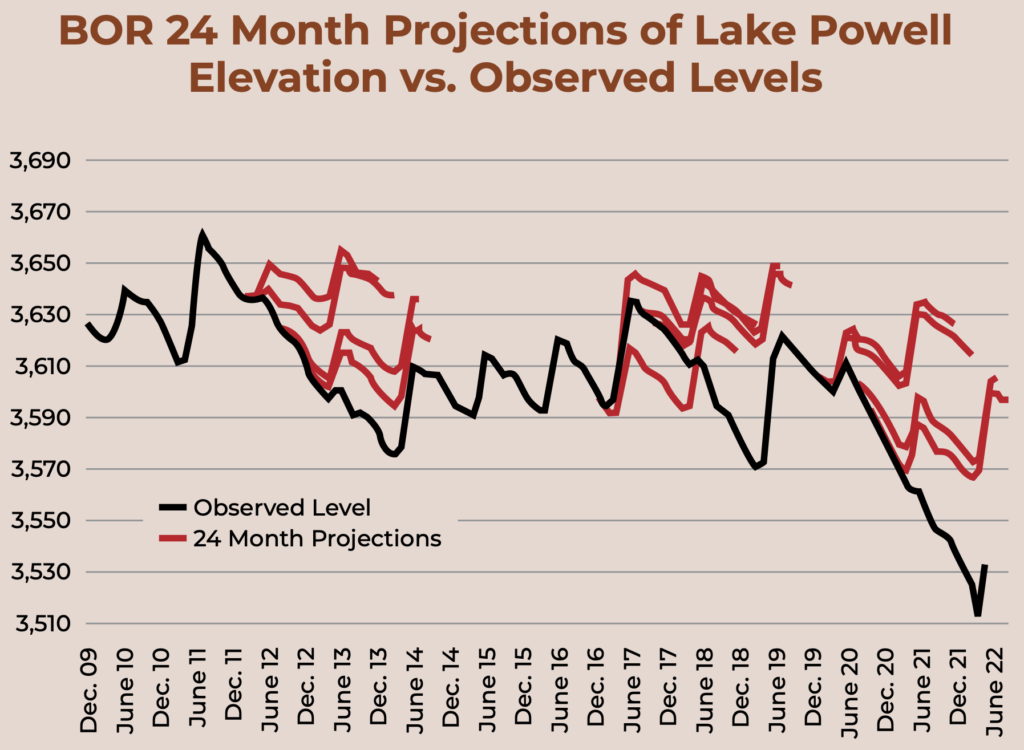

The Bureau of Reclamation’s forthcoming August 24-month study is a key benchmark for managing the nation’s two largest reservoirs – Lake Mead and Lake Powell – but this annual exercise continues to be a problematic endeavor that creates false hopes and unrealistic expectations for the 1 in 10 Americans who live in the Colorado River Basin.

The data in the 24-Month studies trigger cuts under the current management frameworks, the 2007 Interim Guidelines and the 2019 Drought Contingency Plan. The reporting guideposts have veered us in the wrong direction before.

We hope that doesn’t happen again.

Our coalition — made of Glen Canyon Institute, Great Basin Water Network, Utah Rivers Council and Living Rivers/Colorado Riverkeeper — is calling on the Bureau and water managers to do more to plan for a drastically drier future.

Many of the Bureau’s 24-month projections on the Colorado River have drastically over-estimated future Colorado River water flows, particularly during low-flow periods. Climate change is lowering river flows as winter snowpacks are shrinking in the face of warmer winters.

The above chart – made from data from the Center for Colorado River Studies White Paper #7 – highlights the Bureau of Reclamation’s overly-optimistic 24-month projections at Lake Powell (in red) vs actual reservoir levels (in black).

Average flows on the Colorado River since the year 2000 are about 20 percent lower than the last century — with the nation’s top scientists predicting that climate change could reduce water flows an additional 20 percent in the future. After a near-record runoff in 2023, the runoff projections for the 2024 water year estimate that natural flows at Lees Ferry will hover below the 21st century average.

Many water leaders are procrastinating preparing for the impacts of climate change by failing to acknowledge the scope of severity which shrinking snowpacks are causing to the water supply of 1 in 10 Americans.

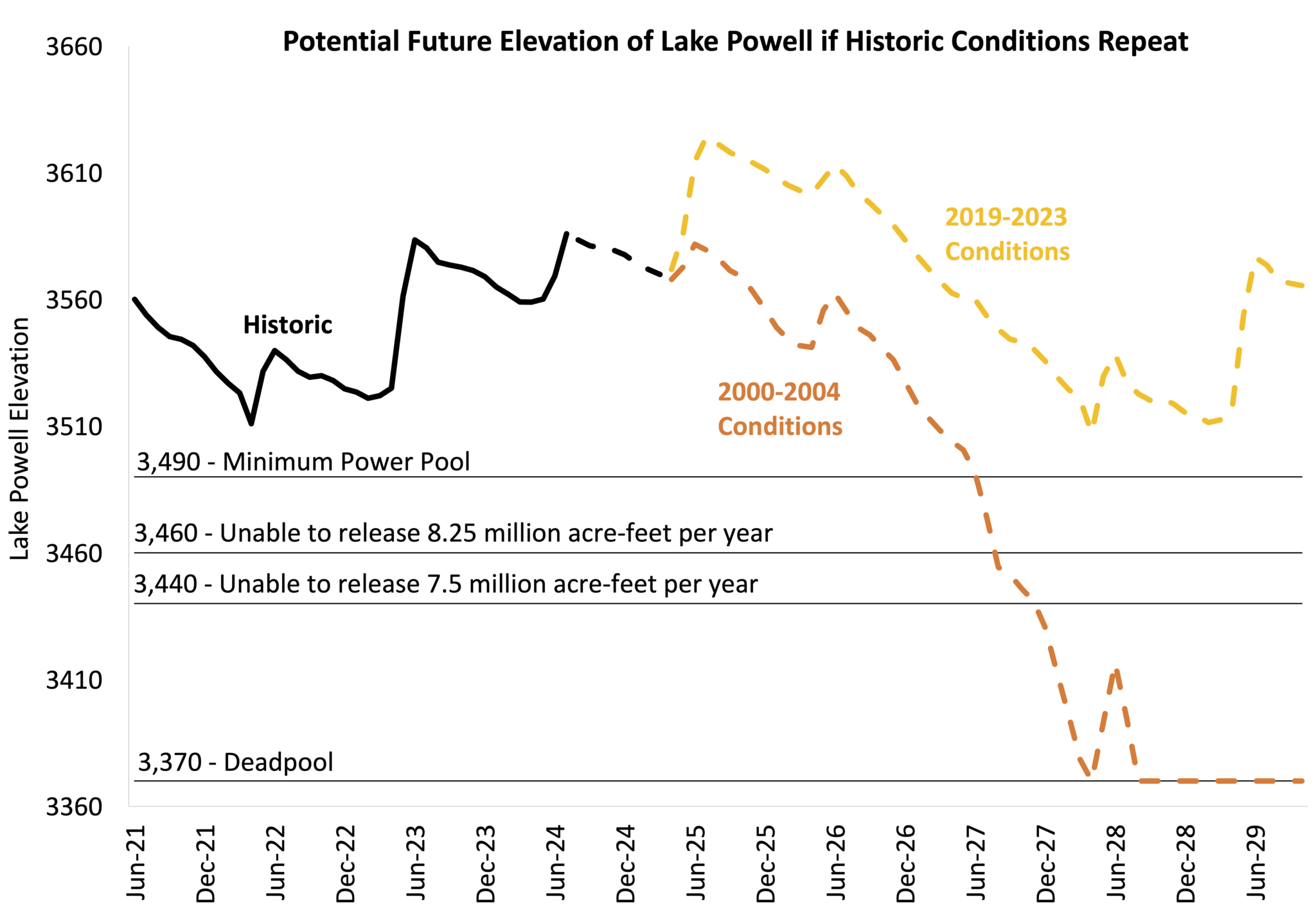

If the drying trends continue, Lake Powell is likely to shrink further in coming years and drop below minimum hydropower generation levels and careen closer to dead pool, creating a water supply crisis that is not being addressed. If Powell reservoir levels drop to 3,490 feet, the seldom-used river outlet works – a set of four small, recently damaged tubes – must deliver water to Lower Basin residents. At low reservoir levels this set of pipes cannot sustain the Upper Basin’s requirement to deliver enough water to Arizona, California and Nevada, in addition to supporting the aquatic ecosystem of the Grand Canyon, to meet the standards under the Law of the River.

The chart above is a hypothetical forecast showing what could happen to Lake Powell water levels in the next five years if we experience several dry years similar to the drought years of 2019-2023 (yellow) or 2000-2004 (orange). The forecast assumes that the Bureau would make similar management decisions, like how much water to release from Lake Powell, in the future as they did in each past historical period. The forecast shows Powell water levels hovering below or slightly above minimum power generation levels.

While we are not using this chart as a promise about what will come, we view it as a means of considering the impacts of really bad winters that may come down the pike. And one of our important takeaways is this:

Not solving Glen Canyon’s plumbing problems threatens to cause even greater drops to Lake Mead water levels moving forward because officials must inflate Lake Powell water levels higher to operate the dam.

As it stands, decreased Lake Mead levels are de facto cuts to Lower Basin states. The inaction in solving Glen Canyon’s plumbing problems could lead directly to water supply reductions in Arizona, Nevada and California that are more problematic than what low reservoir levels will trigger this month — regardless of whatever policies are put in place in 2026 by the seven Colorado River states and the Bureau of Reclamation.

Our coalition is calling for immediate investment for modifications to Glen Canyon Dam to ensure water can reach downstream cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Los Angeles in future dry years. Such modifications will take some 10 years to implement, meaning that postponing a solution to this plumbing crisis only kicks the problem to a future White House.

While this is one of many issues facing water managers on the Colorado River, the antique plumbing problem at Glen Canyon Dam must be a way for us to normalize a likely fact: Lakes Mead and Powell will never be full again in our lifetimes, barring anomalous events. In the water world, long-term agreements are only as good as the near-term weather report. With so much uncertainty, it’s time we dismantle our 20th century notions of long-term thinking and start uplifting the best version of what we can be in the short-term. We have to re-imagine — not double down.

And if we have to choose between operating Lake Powell or Lake Mead in a 20th Century fashion, we take Mead every single time. Millions of people rely on that reservoir for domestic water.

That can’t be said about Powell.

The next 75 years are not going to be like the last 75. That’s as much certainty as we can project.

QUOTES FROM COALITION PARTNERS

“The Bureau’s rosy projections for Lake Powell send the wrong message to the public during the hottest 12-month stretch on record and downplay the impact at Lake Mead,” said Kyle Roerink, executive director of the Great Basin Water Network. “The federal government’s short-term reports create a negative feedback loop that papers over the likelihood of forthcoming dry water years and doubles down on pie-in-the-sky thinking for reservoir management.”

“The Bureau is telling us to expect more big winters, but the data shows the Bureau keeps overestimating future flows” said Eric Balken, Executive Director of the Glen Canyon Institute. “One or two bad winters and we are back in crisis mode at Powell and Mead. That is the real story.”

“We are playing with loaded dice,” said Zach Frankel, executive director of the Utah Rivers Council. “The big winter of 2023 created the misconception that reservoir levels were going to rebound, but America’s two largest reservoirs are only ~37% full. That’s like winning the lottery and still being bankrupt.”

“The Bureau’s projections often make it seem like there will be pots of gold at the end of a rainbow,” said John Weisheit, conservation director of Living Rivers. “But in our warming and drying corner of the world, empty reservoirs are what we will likely find in the years to come.”

To contact Zachary Frankel, call 801-699-1856

To contact Eric Balken, call 801-631-2774

To contact Kyle Roerink, call 702-324-9662

To contact John Wesiheit, call 435-260-2590