In Western water politics, the whiff of money has a way of bringing people together

It is a great unifier.

But, as Wallace Stegner admonished all who live west of the 100th Meridian, there is one “overmastering unity –– the unity of drought.”

The recent deal announced by the Biden Administration and the seven Colorado River Basin States to curb water use between now and 2026 exemplifies how drought and money bring diverse interests together.

It also illustrates how deals hashed in backrooms can garner plenty of headlines – and skepticism. While there were no cloying photo-ops, the press releases elucidated a sense of comfort and relief. But even the central figures in the deal, the Lower Basin States, had to admit during interviews: The deal is a mere stopgap measure.

Our years of taxing the Colorado River won’t be fixed with a billion dollars for fallowing, water banking at Lake Mead, and urban conservation alone. We need to significantly curtail water use across the West. Broken down, the deal only cuts 750,000 acre-feet annually over three-and-a-half water years. The best scientists in the nation say – to stabilize reservoirs – we have to cut some 3 to 4 million acre-feet annually.

Critics across the West are also questioning spending $1 billion on fallowing. But that misses the bigger point: How else will the nation incentivize senior rights holders to give up wet water without getting sued? Conversely, how else will we get water to tribes, those senior rights holders who have had junior entities living off of their entitlements for decades? The question from critics shouldn’t be why $1 billion. The question is: How much more will it take to permanently fix the problem of over-allotment and unjust distribution.

What the critics need to remember: Congress got us into this mess by passing laws that over-developed the river in the 1950s and 1960s. Congress will have to aid in getting us out. The power of the congressional purse will inevitably be one of the most significant tools for drought relief –– and unity.

So why does this deal matter?

First: Irrigators from Imperial Valley reaffirmed a commitment to reduce use by 250,000 acre-feet annually. They have among the strongest rights on the river and are under no legal obligation to take on that cut. It’s also worth noting that those irrigators cut use by 500,000 acre-feet 20 years ago –– transferring the water to LA and San Diego. No single entity has cut more in the last two decades – despite popular belief. And that transfer has led to a disaster at the Salton Sea –– dispelling the notion that taking water away from California agriculture is a silver bullet. But without these folks on board, there would be no deal.

Second: Last month, the Biden Administration released a draft environmental review (SEIS) of two proposals to supplement the existing management framework at Lakes Mead and Powell. Outlined in this proposal were draconian cuts for Lower Basin entities – up to a 4 million acre-feet annual reduction in the Lower Basin in some scenarios. These proposals were destined for litigation. This new deal is a promise that entities won’t start suing each other between now and 2026.

Third: It buys time. The great salve of money helps to make this all palatable. With more than $1 billion from the Inflation Reduction Act, irrigators in Southern California and Western Arizona will be paid to fallow fields and incentivized to make irrigation efficiencies — beginning the path to modernizing agriculture in the Colorado River Basin. It also gives breathing room –– if Mother Nature keeps providing relief –– between now and the 2026 reconsultation deadline.

The Upshot: Mother Nature made this deal possible this winter. But all of this could go out the window if next winter and the following one are bad. The likely outcome in the next few months: The Lower Basin States will tighten up this proposal, give it to the federal government, and have it be subject to an environmental review. Then the federal government will rubber stamp it. After that, all seven Colorado River Basin States will be working toward a long-term deal to manage the reservoirs beyond 2026. Until then, the basin’s water interests will likely be prepping and lobbying Congress to consider long-term Colorado River relief. Additionally, the Upper Basin didn’t contribute a drop of water or anything meaningful to the conversation. That will have to change in the coming years. And it will. They are proposing multiple new dams and diversions upstream of Glen Canyon Dam –– a dangerous prospect as we grapple with curtailment in the Lower Basin.

It is during those long-term negotiations that I expect the unity of drought to fray among the states.

For more info, see GBWN quoted in Marketplace, the Review Journal, Arizona Republic, Deseret News, the Nevada Current, and others.

Utah Invested $500 Million.

Will Nevada Invest Less than One Percent of That?

Vidler/Coyote Springs Stay in the Spotlight

Those interests are holding hostage important and necessary fixes to our water law.

Colton Lochhead reports on the demise of the bill. And, of course, we had plenty to say about it.

BLM Halts Cedar City EIS, More to Come

The BLM’s pausing of the environmental review affirmed what we knew all along: The Central Iron County Water Conservancy District did not have its act together. Its monitoring, management, and mitigation plans are bogus. It willfully ignored senior water rights held by the Indian Peaks Band of the Paiute Tribe of Utah. It did not respect the USGS data that shows the project will draw down the region’s water tables because there are more water rights on paper than in reality.

As I said, anytime the project gets under a real microscope, it crumbles like a stale cookie.

Read the latest on this news from Colton Lochhead in the RJ, and expect more announcements soon.

Where's the Connection Between Scarcity and Equity?

Media reports across the west are hammering on thirsty crops. And while it is tempting to pillory entities that grow water-heavy crops in the desert, we believe that solutions to balancing the rights of water users, the rights of nature, and the rights of communities deserves more than finger wagging in media.

In other words: Pointing fingers won’t point us in the right direction.

The goal of balancing Western water’s supply-and-demand issues should not be expelling families and workers from their homes and land. First, we may not appreciate what replaces them. Second, by displacing the very people who know the land and water systems, we lose knowledge of those systems.

There is an increasingly growing number of reports on how we decrease consumptive uses of water. But not all of them focus on how we prevent leaving rural – often disadvantaged communities – left out to dry.

The Union of Concerned Scientists offers new analysis on this matter. It has some flaws and gaps. But it provides a lens to assess water scarcity, emissions reductions, improved health, and new prosperity for communities.

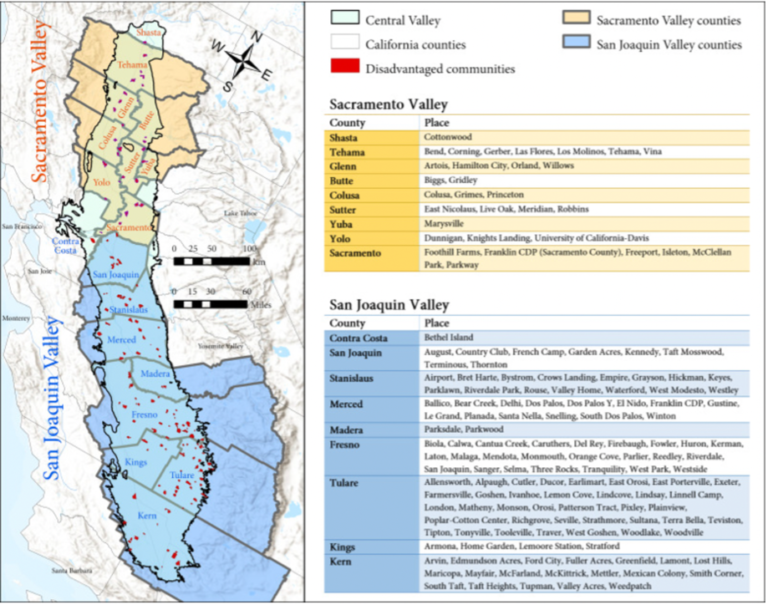

The new report takes a hard look at California’s Central Valley and posits: Communities can reduce groundwater overdraft, water contamination, and carbon emissions by putting buffers (renewable energy developments and groundwater recharge projects) each within one mile of 154 towns in the region. The analysis claims that this will increase revenue to ag operations because the renewable energy developments on private lands will subsidize any agricultural production that ceases.

Ultimately, this is about how fields fallow in order to save water. It is also about keeping communities intact while preparing for the hard times ahead. The Great Basin and Colorado River Basin could benefit from similar analysis.

That is all we have for this week. Thank you, as always, dear reader, for your time and interest. We cannot do what we do without you.

And remember, the sand stays, the water goes.

Kyle