The federal government allows only one state in the west to profit from public land sales, and it happens to be the driest: Nevada.

The policy’s legacy is one where billions of dollars flow into government coffers to pay for things that Congress and the state legislature won’t in Nevada. The acute addiction to the money provokes calls from all corners of the state to double down on the policy and put up more arid public lands for auction.

Now, as Senator Catherine Cortez Masto leads a powerful cohort of interests asking Congress for more land, there are growing concerns from the public about expanding the law as the water supply and climate feel ever more precarious.

The Senator’s push raises questions about the policy’s boosters who claim dire urgency to sell off more land. Hundreds of millions of dollars remain available for Nevada communities from the existing program and thousands of acres maintain eligibility for the Bureau of Land Management to auction off to private interests.

But a major development push for an additional airport and more sprawl south of Las Vegas are underlying the efforts. And the promise of future money in a cash-strapped state bedazzles the interests that are looking to make a quick buck and forever transform the landscape of the Mojave Desert.

GBWN believes the policy and its proposed expansion elevate myopic planning ahead of pragmatic gut checks about what the future holds for places like Las Vegas and all corners of the state. The uncertainty about water should give Senator Cortez Masto pause and end her quest to pass her expansive bill. Public lands selloffs must not be the future of resource management policies in the Colorado River Basin and Great Basin. They are rooted in a much different past. And if history is any indicator, Las Vegas is a hotter, drier, more polluted place than it was before the land sales became law. Repeating mistakes will exacerbate, not mitigate, the problems we face.

Read our deep dive below, digest our charts, and be sure to tell Senator Cortez Masto to withdraw her bill.

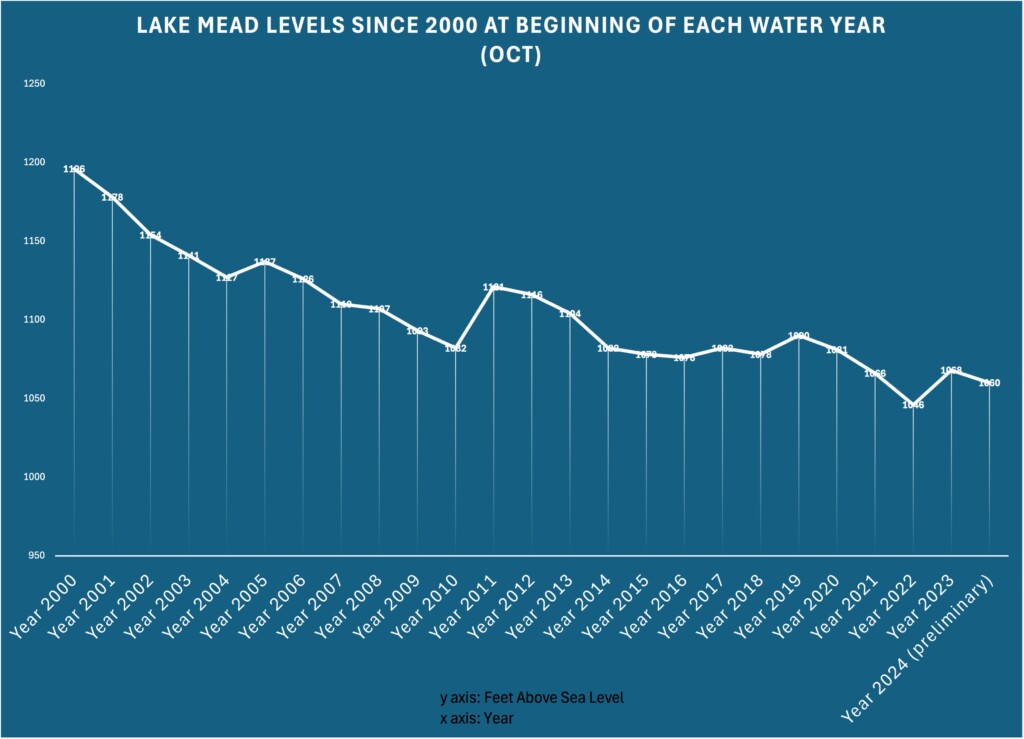

CHART 1: LAKE MEAD ISN’T FILLING ANYTIME SOON

When the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act (SNPLMA) passed in 1998, Lake Mead was nearly 100 percent full and the population was 1.1 million. Now, an additional 1 million people depend on the vulnerable reservoir that’s lost two-thirds of its contents in the past 24 years.

Today the elevations are down more than 130 feet from 24 years ago. And most experts agree: The Colorado River will not be filling the nation’s largest reservoir again in our lifetime.

In May, Senator Cortez Masto re-introduced her expanded SNPLMA bill, the Southern Nevada Economic Development and Conservation Act, after an average winter failed to provide Lake Mead with a meaningful boost.

Senator Cortez Masto’s bill to broaden the public-land-sale policy could help deliver an additional 800,000 people or more in Southern Nevada during the coming decades.

The bill also paves the way for the Southern Nevada Water Authority to build a pipeline that would be the backbone of new Colorado River water deliveries for sprawl spanning dozens of miles to the California border. There are mountaintop conservation designations that will do little to mitigate the traffic, pollution and water use the bill inevitably generates. There will be nominal efforts made to build affordable housing.

SNPLMA is not far from what the sagebrush rebels always wanted. But instead of cattlemen getting the ability to acquire public land for private interests, we hand the desert over to urban movers and shakers. And the political class — Democrat and Republican — bend over backwards to make it happen.

TABULA RASA

A large chunk of the land proposed for disposal will be part of a bigger push to develop Jean Lake Valley, Hidden Valley and Ivanpah Valley into a new transportation, residential, commercial and industrial corridor in Southern Nevada.

Congress approved public land transfers for a massive 23,000 acre supplemental airport in Ivanpah in the early 2000s — a foothold that will catalyze development from Primm to Henderson if the new bill passes.

The expansive sprawl bill will help bridge the targeted valleys, creating a blank canvass for developers to reshape the Mojave Desert and leaving the community on the hook for new infrastructure needs that the tax base won’t be able to cover. The need for money will swell as the plans for Southern Nevada’s expansion stretch. The pipelines, roads, power lines and other necessary services will not be cheap or climate friendly. As history has shown, Clark County can’t meet the excessive infrastructure costs that the new sprawl brings — forcing governments to rely on regressive sales taxes, nickle-and-dime fees, and, of course, the SNPLMA money. This is underscored by years’ worth of sales taxes hikes for water, fuel, education and other government obligations.

MONEY FOR WATER

Clark County is somewhat transparent about its plans. Local officials recently approved funding for an environmental review of the airport and this week there was a public meeting highlighting some of what the Senator’s bill would do.

Consultants admitted that new sprawl would consume about 10 percent of Nevada’s annual share of the dwindling Colorado River (We haven’t checked their math yet).

Nevertheless, at a recent press event, the SNWA’s long-time DC lobbyist told a gaggle of reporters in the spring — residents don’t have to worry about water.

Really?

Despite our legal victories to stop the Vegas pipeline, the SNWA maintains a massive agricultural operation in Eastern Nevada that spans some 900,000 acres.

The authority still grows alfalfa with ground and surface water. It runs livestock. And it engages heavily in land management matters throughout Lincoln and White Pine Counties.

The big city water agency keeps these assets as an investment for the future — not as a play on commodities like beef, lamb, wool and leather.

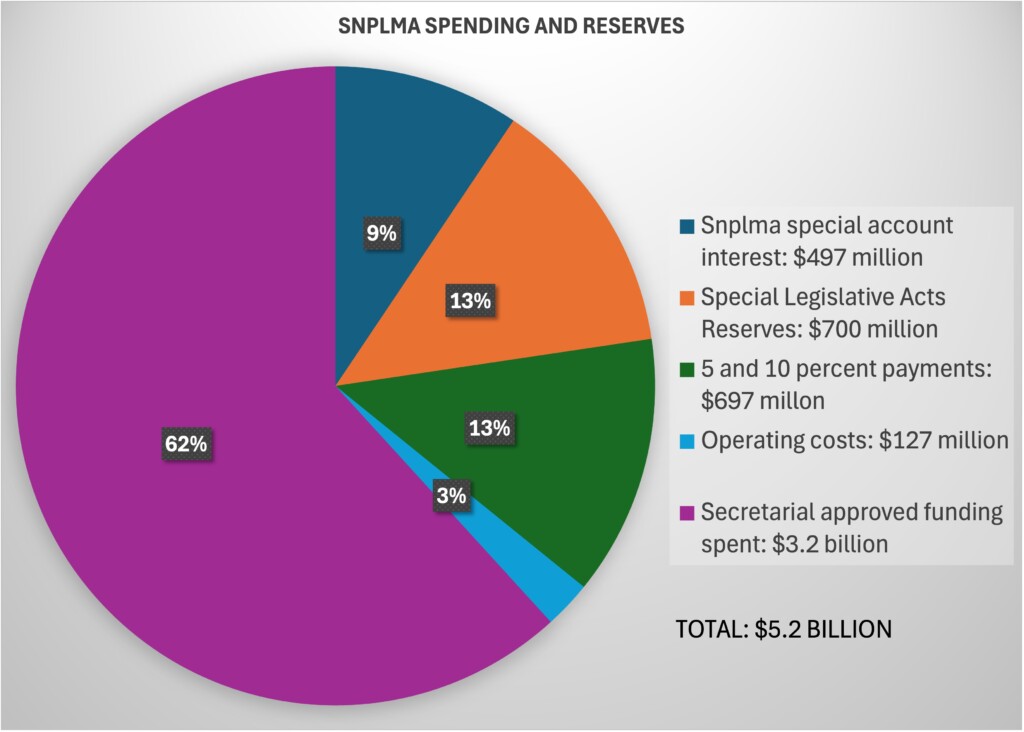

CHART 2: SNPLMA HAS GENERATED BILLIONS, CAN IT LAST?

Since 1998, federal lawmakers have set aside more than 67,000 acres of public lands in Clark County that are eligible for auction to private interests — with 22,000 acres having been sold. Another 18,000 acres are tied up in leases, exchanges, reserves and other management vehicles out of federal jurisdiction.

While 27,000 public acres remain available for auction under existing statute, Senator Cortez Masto’s new bill asks for at least 25,000 additional acres for disposals that would be added to the remaining acreage not yet sold.

But the acreage is a minor detail when compared with the vast sums of money that could be garnered.

The law generated more than $5 billion since its passage in 1998 from selloffs and interest generated by the “Special Account” that holds the funds.

RURAL NEVADA LOVES THIS POLICY TOO

Right off the top, SNPLMA directs 10 percent of public land sale proceeds to the SNWA and 5 percent to the state of Nevada. Then local entities can apply with the BLM for funding.

Clark County has immensely benefited from the proceeds — funding conservation projects and capital improvements throughout the region.

However, it is not just Southern Nevada that’s addicted to the law. It’s rural governments too.

A review of the 1998 law and the decades of spending show that rural and urban Nevada both benefit from selling off public lands and inviting the masses to the Mojave Desert.

The billions of dollars generated by land sales are doled out to other communities in the state, creating a flow worth millions of dollars and a dependence on a law that actively exacerbates what many rural Nevadans fear: an uncontrollable and thirsty growth machine in Vegas.

SNPLMA is a conundrum in the state with the most federally managed land in the contiguous U.S. In the years prior to SNPLMA, there were concerns that Las Vegas would run out of developable land. In 1980, the precursor bill to SNPLMA, Santini-Burton, offered a mere 7,000 acres of disposal land when there was an actual threat of losing all private land.

Now we are on the path toward increasing that figure of eligible land for sale by more than 1,200 percent since Santini-Burton.

And other states are taking notice. Reno and Washoe County are pursuing their own version of SNPLMA, having enlisted the support of Senator Rosen and local officials. Utah’s Senior Senator Mike Lee is eying his own version of SNPLMA too.

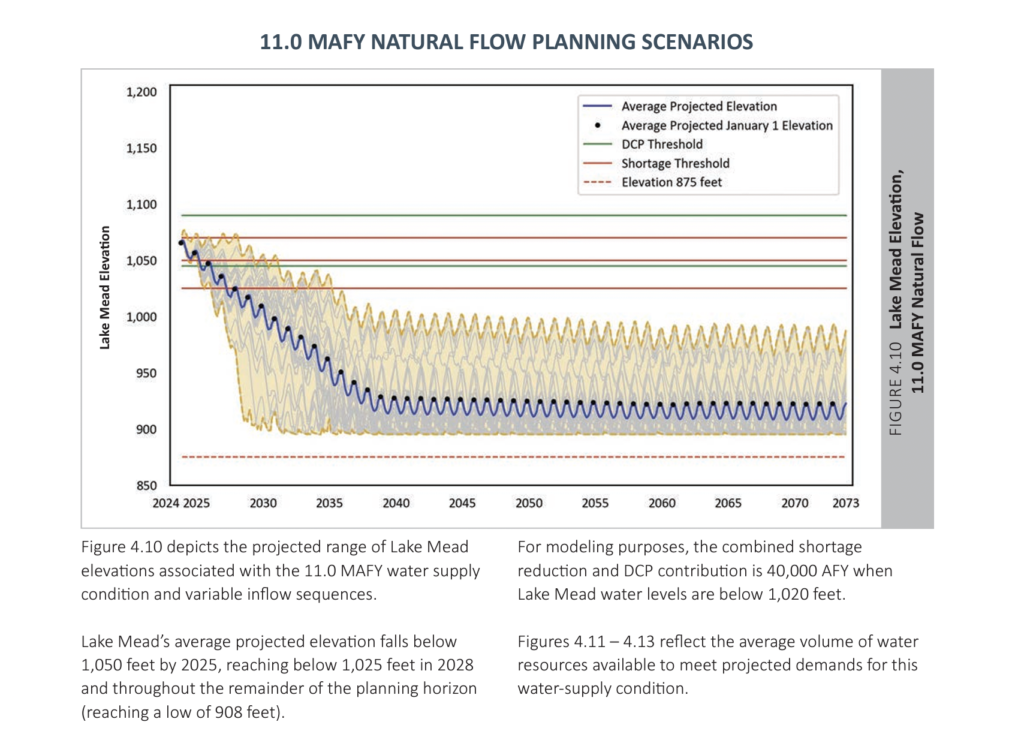

CHART 3: THE OUTLOOK IS DRY EVEN IF IT RAINS MONEY

***NOTE ON CHART 3: The above image is a model run done by the SNWA in its 2024 Water Resource Plan, the agency’s long-term outlook that it publishes annually. This chart shows dropping Lake Mead elevations in the coming decades and then a flat line that is indicative of far-off uncertainty as much as anything else. This planning scenario uses an 11 million acre foot average flow benchmark as a worst case scenario. But scientists expect that flows could bottom out at nine or ten million acre feet between now and the end of the century, meaning that the situation at Mead could be much worse.

Cortez Masto’s bill will bring more money over time. But it won’t elevate Lake Mead’s levels.

With the new bill, lawmakers will be deciding to take the river where it’s never been before.

The chart above is one way of showing a variety of scenarios, many of which show Lake Mead’s elevations hovering between 950 and 900 feet in elevation — a scary drop from its current levels.

But those scenarios from the SNWA are not even a worst-case prospect.

The nation’s top scientists believe that the Colorado River could be down 40 percent from the 20th Century average in the coming decades. If that were included in the modeling, things would look even worse.

Hard-working, blue-collar Nevadans are not the ones pushing this bill — with the concerns from residents paralleling the scientific outlooks on the Colorado River. A recent letter to the editor in the Las Vegas Review Journal summarized the situation quite well:

We do a great job conserving water in Southern Nevada, but it seems the more we try to save, the more is consumed by new housing. If the federal government and Congress agree the drought will intensify, why are we allowing the building of thousands of homes each year? It doesn’t make sense.

People don’t mind conserving. But for whom are they doing it? Ripping out turf for new homes is not the same as ripping it out for Lake Mead.

We have slim margins of error to protect current and future residents from rising water costs and hardships imposed by scarcity. We cannot invite more people to a desert and expect water to magically appear at Lake Mead. We need a NEW way forward that isn’t in lockstep with an OLD guard intent on mortgaging Vegas’ future with public-land selloffs.

Fresh ideas are sorely lacking. Before expanding the law, let’s exhaust all resources associated with the existing SNPLMA program. Then, when the money and land are gone, the public can consider what it wants to do.

We can’t turn back the clock on SNPLMA. But we can turn a new page on how we fund future priorities.

Tell Senator Cortez Masto to withdraw her bill.